Go × Clean Architecture implementation pattern

Click here for Japanese version

What is Clean Architecture?

It could be thought an architecture pattern that dissociates interest by realizing:

- Make domain logic independent

- Make framework independent

- Make UI independent

- Make any external agency independent

- Make domain logic easier to test

you may refer to various articles for further details, and we will focus on discussing about implementation patterns.

Sample App

It just can be used to register user by posting to /users and is based on manuelkiessling/go-cleanarchitecture and using gorm as an ORM.

App Architecture

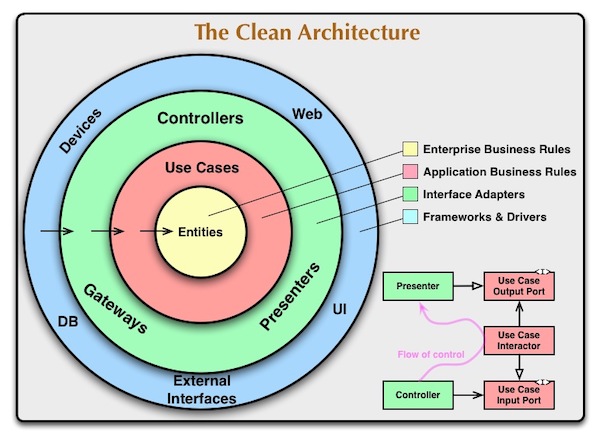

Generally, it can be divided into any layers, but you should divide according to “Common Closure Principle (CCP)”; it means bunching up the components that could be changed for the common reason. This time, I divided it into four layers according to original text.

Be sure to make dependencies keeping in a single direction from the outside to the inside, here’s the bottom line.

Directory structure

pkg

├── adapter

│ ├── controllers

│ ├── gateway

│ └── interfaces

├── domain

├── external

│ ├── mysql

└── usecase

└── interfaces

The chart below shows the relationship between the directories and their roles.

| Directory | Layer |

|---|---|

| external | frameworks & drivers |

| adapter | interface adapters |

| usecase | app business rules |

| domain | enterprise business rules |

Be thorough on dependency

I’ve got to walk you through an essential rule before entering the implementation explanation.

As mentioned earlier, dependencies must be kept in a single direction from the outside to the inside. On the contrary, any program has inputs and outputs, and scenes where the results processed inside are output to the outside frequently appear — that is, the scene that you want to depend on from the inside to the outside is typical. Solving the contradiction using the dependency inversion principle will be the key to keeping the clean architecture clean.

What is dependency inversion principle?

Briefly, the principle is that inside should not depend on the outside, but should depend on abstraction. It would be tough to understand, so let’s actually look at the code.

func (i *UserInteractor) Add(u domain.User) (int, error) {

return i.UserRepository.Store(u)

}

The above represents the second layer from inside, the implementation of the app business rules layer. It can be used to try to store the userinfo into the DB outside. In this scene many people tend to do accessing the outer layers directly, but you’ve got to avoid that in order to make inside not dependent on outside.

The key to solving that is the dependency inversion principle, you can realize it by defining the interface.

type UserRepository interface {

Store(domain.User) (int, error)

FindByName(string) ([]domain.User, error)

FindAll() ([]domain.User, error)

}

The repository interface should be defined in the same layer so that it depends on this interface. And concrete type can be kept dependency from inside to outside by passing from the outside.

This is the dependency inversion principle. You’d better see here for better understanding.

Implementation example of each layer

The implementation of the inner two layers typically can be changed depending on the project; we will focus on the outer two layers.

routing

It was actually implemented with gin for WAF, but it’s easy to replace because this layer uses it as a tool. Also, the fact that concrete type such as DB connection and logger etc are passed to inside in this layer realizes dependency inversion principle.

var Router *gin.Engine

func init() {

router := gin.Default()

logger := &Logger{}

conn := mysql.Connect()

userController := controllers.NewUserController(conn, logger)

router.POST("/users", func(c *gin.Context) { userController.Create(c) })

Router = router

}

ORM

ORMapper is defined in Adapter layer.

In this case, I am devoted to solving the impedance mismatch by converting the DB optimized type to the type optimized for domain logic.

The adapter layer actually depends on abstraction and the interface defined in this layer depends to some extent on the outer library.

In principle, I looked at the following is defined:

‘Abstract’ should not depend on implementation details

The role of this layer is conversion; it would be natural to know both sides to some extent.

Please let me know if you know a better implementation pattern here.

type (

UserRepository struct {

Conn *gorm.DB

}

User struct {

gorm.Model

Name string `gorm:"size:20;not null"`

Email string `gorm:"size:100;not null"`

Age int `gorm:"type:smallint"`

}

)

func (r *UserRepository) Store(u domain.User) (id int, err error) {

user := &User{

Name: u.Name,

Email: u.Email,

}

if err = r.Conn.Create(user).Error; err != nil {

return

}

return int(user.ID), nil

}

Conclusions

As you can see, it is just too large to make REST api just to register userinfo.

You can separate concerns by abstraction, yet would it be worth that much effort to you? You’ve got to think carefully. It would be often that there is no effect if the application size is small since the code becomes complicated basically when it abstracts.

It would be greatly appreciated if you could point out if there is something wrong.