Understanding how AES encryption works

I recently had the opportunity to encrypt/decrypt stuff using AES, but I didn’t know it inside out well. I couldn’t help but be curious about how it is working, and I realized my mind could only be satisfied by digging deeper into its implementation. This post walks you through how AES encryption works by reading core implementation written in Go.

What is AES encryption?

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is a symmetric block cipher, an alternative to the DES. Cryptographers from around the world proposed algorithms, from which the Rijndael algorithm was selected in 2000. Hence we’ll take a look the implementation of this Rijndael.

Rijndael

Rijndael is a block cipher algorithm. A block cipher is a cryptographic algorithm that processes a specific number of bits at a time. The number of bits (called block length) to be processed at a time depends on the algorithm, AES is 128-bits (16-bytes). Most plaintext we encrypt is longer than this block length, so we typically use this block cipher algorithm repeatedly. Keep in mind this post goes into some details on only on one block’s process to focus more on the core algorithm.

Digging deeper into the implementation

The Go language officially provides the crypto/aes package, which makes use of Go Assembly to leverage Intel’s hardware support for AES if it’s built for amd64. It otherwise uses the implementation written in pure Go. Let’s take a look at the pure Go implementation that the human mind relatively can work in.

The public method aesCipher.Encrypt defined in aes/cipher.go looks to implement a block cipher:

// The AES block size in bytes.

const BlockSize = 16

func (c *aesCipher) Encrypt(dst, src []byte) {

if len(src) < BlockSize {

panic("crypto/aes: input not full block")

}

if len(dst) < BlockSize {

panic("crypto/aes: output not full block")

}

if subtle.InexactOverlap(dst[:BlockSize], src[:BlockSize]) {

panic("crypto/aes: invalid buffer overlap")

}

encryptBlockGo(c.enc, dst, src)

}

This method does the two validations that check if:

- the given plaintext is equal to 16-bytes, the block length of AES

dstandsrcshare memory at any index

It seems to leave the core implementation to encryptBlockGo defined in aes/block.go:

// Encrypt one block from src into dst, using the expanded key xk.

func encryptBlockGo(xk []uint32, dst, src []byte) {

_ = src[15] // early bounds check

s0 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[0:4])

s1 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[4:8])

s2 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[8:12])

s3 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[12:16])

// First round just XORs input with key.

s0 ^= xk[0]

s1 ^= xk[1]

s2 ^= xk[2]

s3 ^= xk[3]

// Middle rounds shuffle using tables.

// Number of rounds is set by length of expanded key.

nr := len(xk)/4 - 2 // - 2: one above, one more below

k := 4

var t0, t1, t2, t3 uint32

for r := 0; r < nr; r++ {

t0 = xk[k+0] ^ te0[uint8(s0>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s1>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s2>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s3)]

t1 = xk[k+1] ^ te0[uint8(s1>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s2>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s3>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s0)]

t2 = xk[k+2] ^ te0[uint8(s2>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s3>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s0>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s1)]

t3 = xk[k+3] ^ te0[uint8(s3>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s0>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s1>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s2)]

k += 4

s0, s1, s2, s3 = t0, t1, t2, t3

}

// Last round uses s-box directly and XORs to produce output.

s0 = uint32(sbox0[t0>>24])<<24 | uint32(sbox0[t1>>16&0xff])<<16 | uint32(sbox0[t2>>8&0xff])<<8 | uint32(sbox0[t3&0xff])

s1 = uint32(sbox0[t1>>24])<<24 | uint32(sbox0[t2>>16&0xff])<<16 | uint32(sbox0[t3>>8&0xff])<<8 | uint32(sbox0[t0&0xff])

s2 = uint32(sbox0[t2>>24])<<24 | uint32(sbox0[t3>>16&0xff])<<16 | uint32(sbox0[t0>>8&0xff])<<8 | uint32(sbox0[t1&0xff])

s3 = uint32(sbox0[t3>>24])<<24 | uint32(sbox0[t0>>16&0xff])<<16 | uint32(sbox0[t1>>8&0xff])<<8 | uint32(sbox0[t2&0xff])

s0 ^= xk[k+0]

s1 ^= xk[k+1]

s2 ^= xk[k+2]

s3 ^= xk[k+3]

_ = dst[15] // early bounds check

binary.BigEndian.PutUint32(dst[0:4], s0)

binary.BigEndian.PutUint32(dst[4:8], s1)

binary.BigEndian.PutUint32(dst[8:12], s2)

binary.BigEndian.PutUint32(dst[12:16], s3)

}

Don’t be afraid of it. We’ll focus on the significant parts.

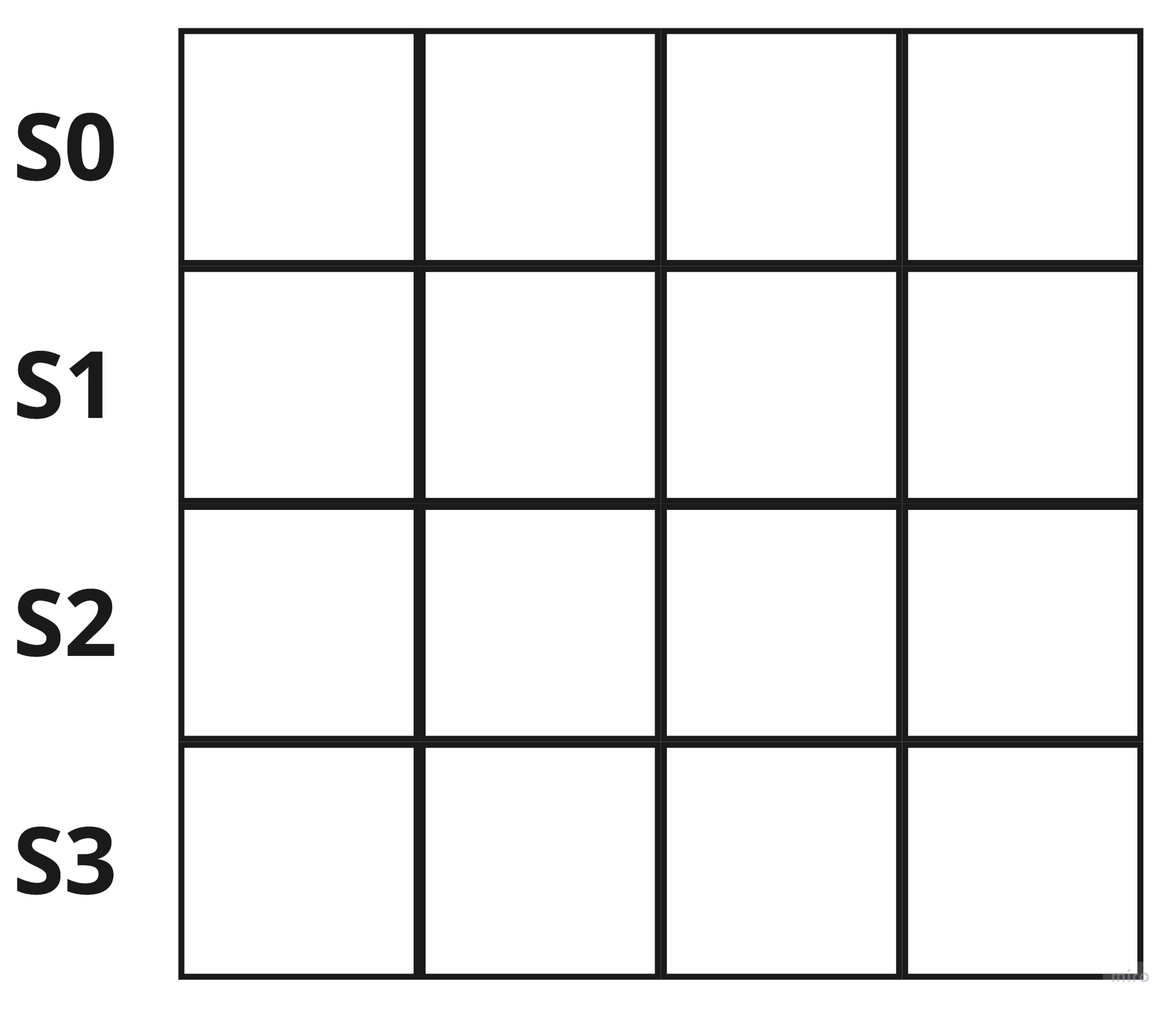

The input (means plaintext) to a single block is 16-bytes as we can see above. The input is first divided into four lines, separated by four bytes.

s0 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[0:4])

s1 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[4:8])

s2 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[8:12])

s3 := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(src[12:16])

This illustrates how the input is handled in the AES encryption process. It is definitely the key to understand to keep this format in mind.

And the next part which is something iterating, is the most core implementation.

// Middle rounds shuffle using tables.

// Number of rounds is set by length of expanded key.

nr := len(xk)/4 - 2 // - 2: one above, one more below

k := 4

var t0, t1, t2, t3 uint32

for r := 0; r < nr; r++ {

t0 = xk[k+0] ^ te0[uint8(s0>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s1>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s2>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s3)]

t1 = xk[k+1] ^ te0[uint8(s1>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s2>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s3>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s0)]

t2 = xk[k+2] ^ te0[uint8(s2>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s3>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s0>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s1)]

t3 = xk[k+3] ^ te0[uint8(s3>>24)] ^ te1[uint8(s0>>16)] ^ te2[uint8(s1>>8)] ^ te3[uint8(s2)]

k += 4

s0, s1, s2, s3 = t0, t1, t2, t3

}

Rijndael encrypts a block by repeating a process called a round. In a round, there are four processes: SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, and AddRoundKey. As commented out in the snippet, the number of rounds depends on the key length.

SubBytes

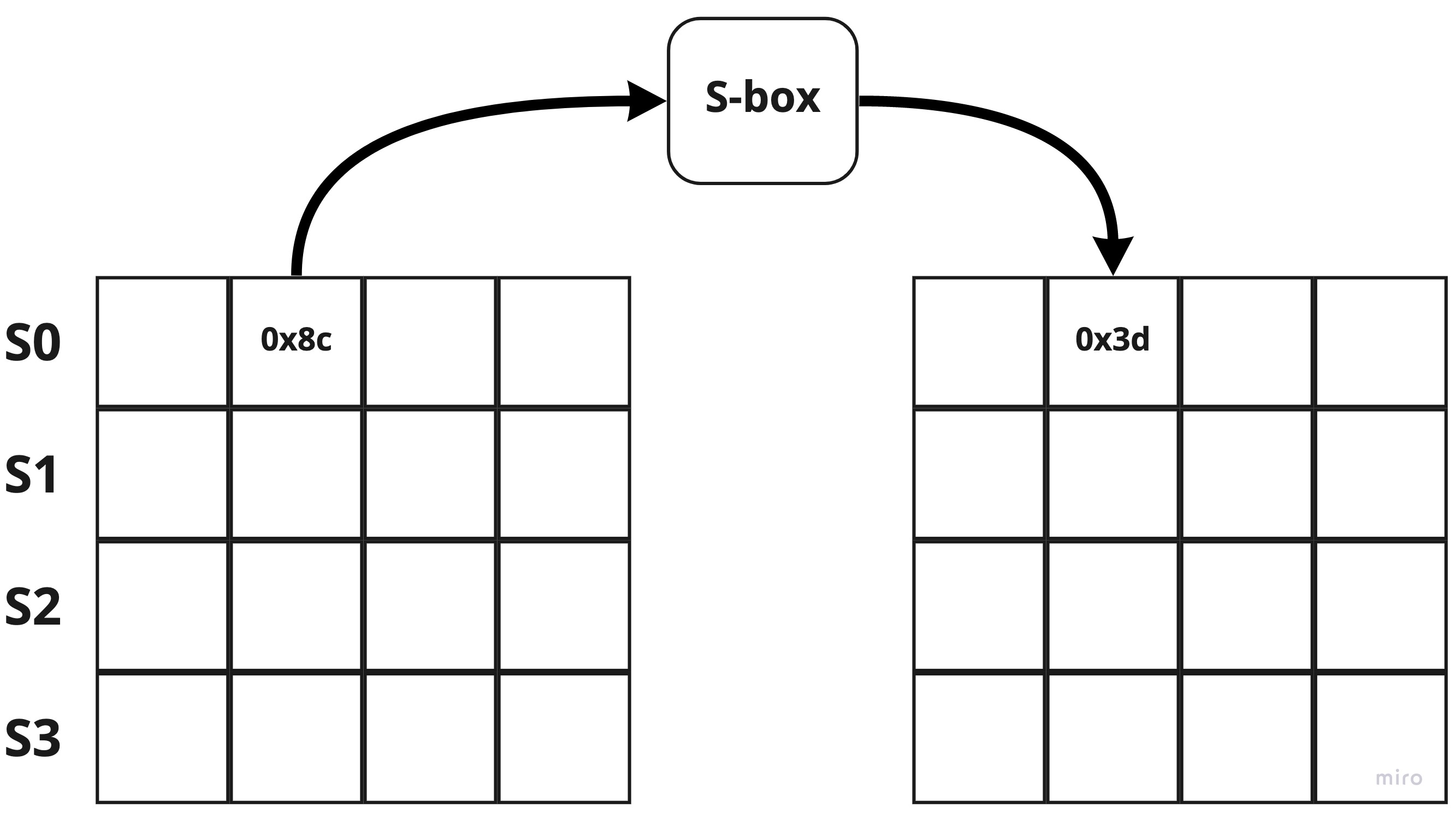

The conversion is done 1-byte at a time based on a conversion table called S-box which has 256 values.

Below illustrates to perform sbox[s0[1]] well:

Unlike DES, we can see that all bytes have been converted at this point. This post doesn’t cover AES’s S-Box as it is mentioned in many places and much better than I could do.

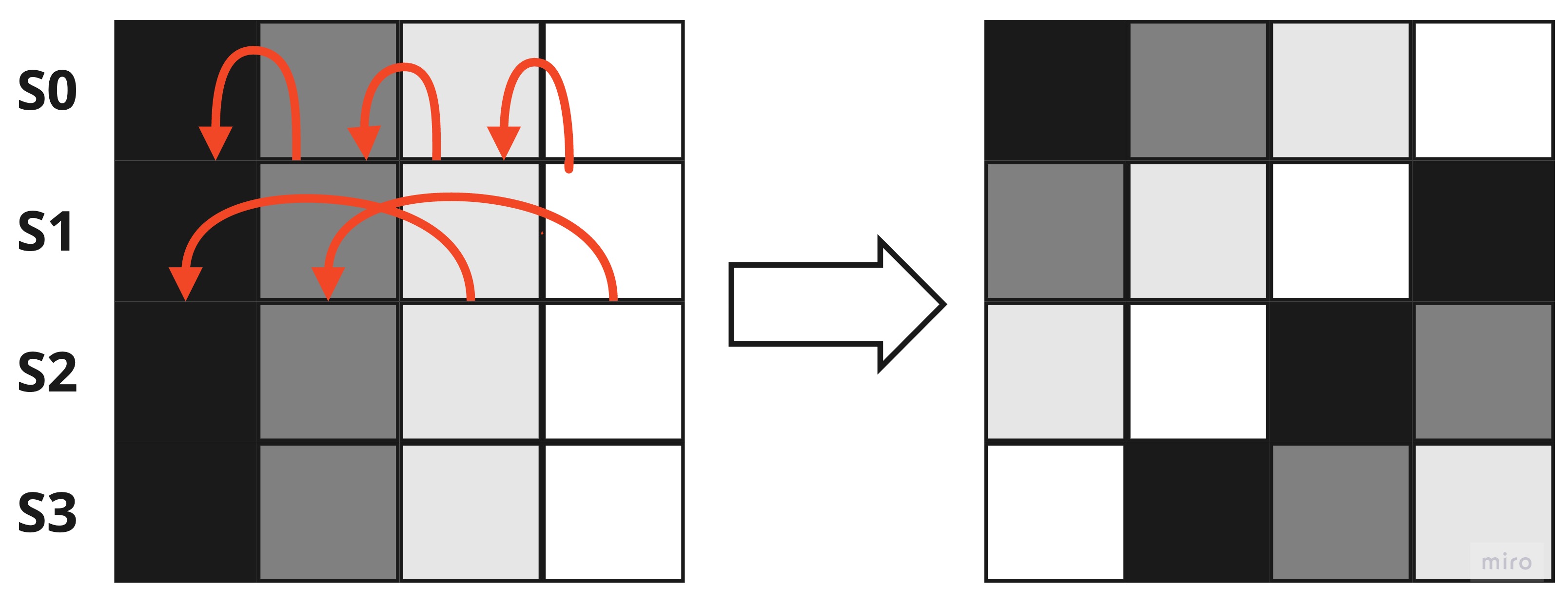

ShiftRows

The next step is to process the rows that are grouped into 4-byte units and shifted regularly to the left. The number of bytes to be shifted depends on the line, as shown below:

MixColumns

In the previous step, it dealt with rows, but the next is to process the bytes in columns.

It involves multiplication operations in a finite field, hence this step is a bit tough to describe. See Wikipedia for more details.

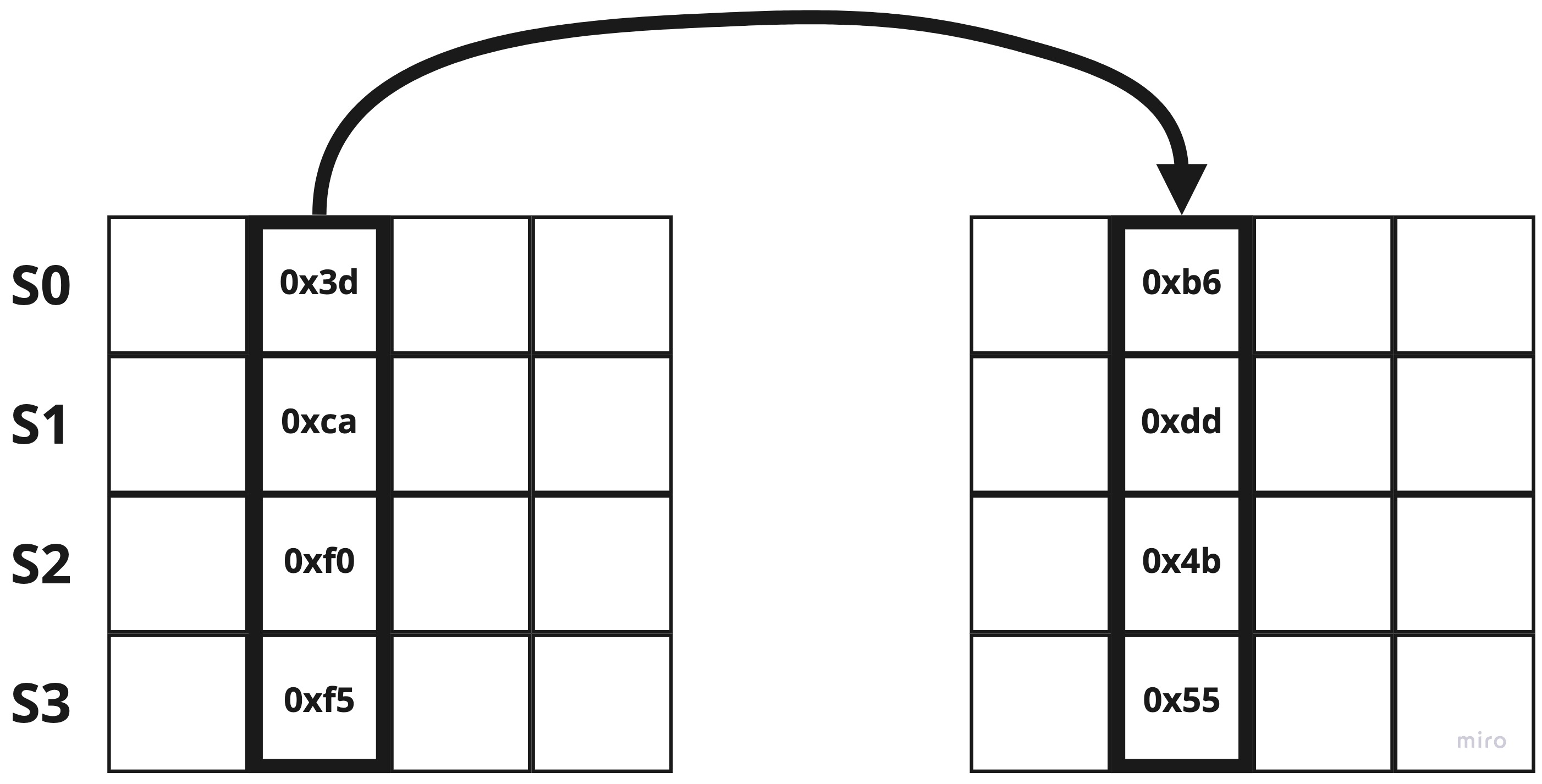

AddRoundKey

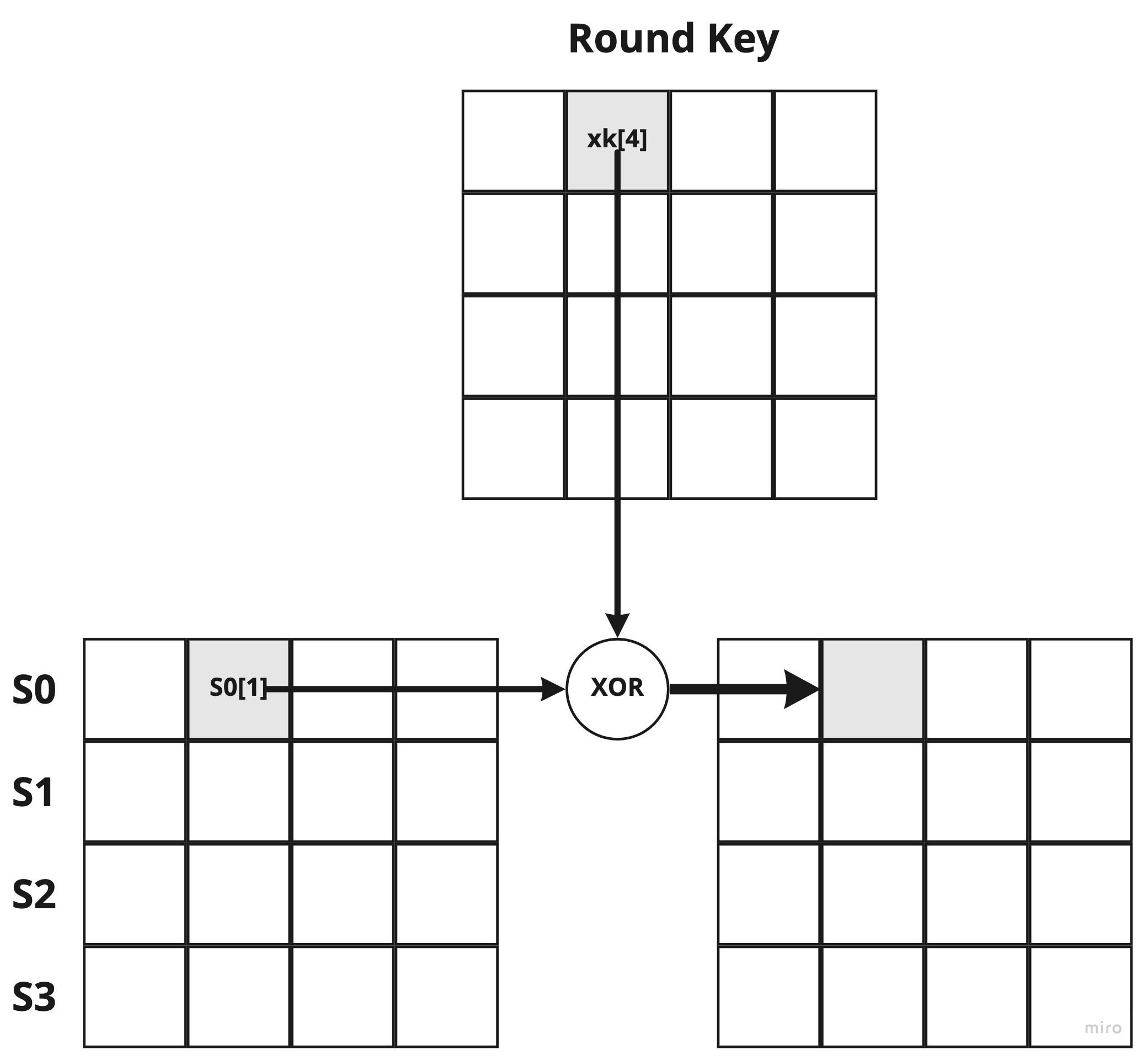

Finally, it XORs the output of MixColumns with the round key. The following figure shows the execution of s0[1] ^ xk[4] (the ^ denotes an XOR operation in Go).

Bottom Line

While this post has only shown you the encryption process, these processes are fully reversible with an Inverse MixColumns, ShiftRows, SubBytes. How beautiful! I’ll keep reading the implementation to deepen my understanding of cryptography.